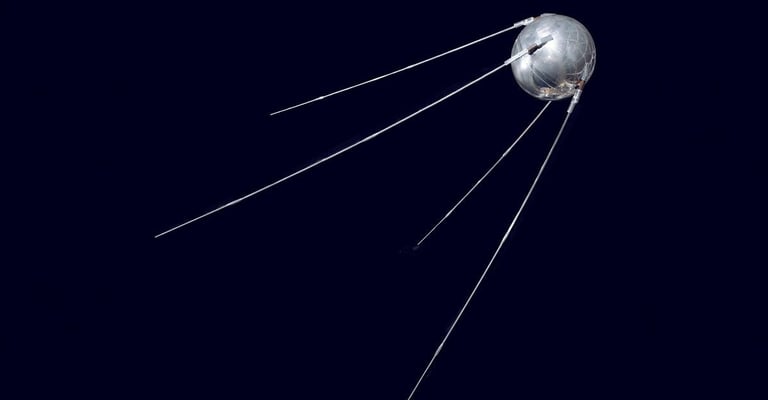

In the middle of the desolate Kazakhstan steppes, during the night of October 4/5 1957, a Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile was launched into space carrying a 183 pound steel ball with a simple radio transmitter tucked inside. Suddenly the future was Russian.

For countries learning to live with the threat of nuclear war, the military implications were terrifying. For the Soviets, Sputnik proved that Communism worked and that world domination was possible. But for the US the aftermath was shattering - in a matter of hours they had lost their unrivaled world supremacy and much of their self-confidence with it. The launch of Sputnik truly marked the end of the "American century."

Drawing on classified documents and interviews with those involved in the launch of Sputnik and the aftermath, Jeffrey Robinson brings to life the political maneuvers and hidden agendas of the Cold War.

He reveals how US President Dwight Eisenhower plotted the invasion of Russia, how British PM Harold Macmillan used Sputnik to bring American atomic weapons to British shores, and how Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev armed one ICBM with a nuclear warhead, set the guidance system to target the US and brought the world to within one hour of atomic holocaust.

A world-class investigative thriller, The End Of The American Century is a shocking tale of private obsessions and public paranoia, of power- games, slapstick, miscalculations and the ultimate brinkmanship.

MY PERSONAL SPUTNIK STORY

Throughout that weekend in October 1957, I remember well the sense of panic in the United States that the Russians might have put a bomb in orbit to blow up New York or Washington.

Oddly, the only person who didn’t seem bothered by it was President Dwight David Eisenhower. He knew there was no real threat because he had U-2 spy plane photos that showed no other missiles, and therefore no other satellites, ready to go from the Baikonur launch site.

The local New York papers ran stories explaining how to see Sputnik. It would pass through the night sky at a certain time and if you looked in a certain part of the sky, sure enough, there it was. A steady light moving across the night. Which is how every New Yorker of my generation can claim we saw Sputnik.

Except, none of us actually did.

Sputnik itself was the size of a beach ball, only 23” in diameter. What we saw, instead, was the sun’s reflection off the missile’s nose cone that had also been blasted into orbit.

Sill, I was so convinced that I had spotted it, my parents gifted me an almost life-sized model of Sputnik, which I dutifully put together with glue and the patience of a Russian engineer, then hung it from the ceiling of my bedroom. There it gathered dust until I went off to college and my mother made my Sputnik disappear.

Nevertheless, my fascination with Sputnik did not dissipate over the years and, more than three decades later, actually shifted into even higher gear when I met a Russian man in London who told me he’d been peripherally involved with various aspects of the project.

One of the things he liked most about it, he said, was that the Soviets had panicked the Americans into believing it was something much more than it actually was. He told me, “What no one in America knew was that Sputnik was only an after-thought to the missile program. It was little more a huge bluff.”

Huh?

The engineer in charge of designing Soviet missiles which were intended to, someday perhaps, bomb American cities, was Sergei Korolev. His job was to build an ICBM that could reach New York and Washington. But Korolev was also a dreamer and at one point he approached the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, to ask a favor. He said, what he wanted to do, when he tested the missile, was also to put a satellite in orbit. Khrushchev wasn’t in the least interested. But Korolev insisted and, finally, perhaps just to get rid of him, Khrushchev said, OK, you can do your satellite thing but don’t screw up the missile.

So Korolev set about designing a system to put a tiny steel ball with a radio transmitter into space orbit.

Now, my new Russian friend asked, how long do you think the entire satellite program lasted? How long did it take Korolev to design it and put it into orbit?

I’d heard estimates of more than ten years. I settled on, three to five.

He told me, three weeks.

Korolev realized that all he had to do was install a transmitter inside the ball, then place a blasting cap on the nose cone to blow it open at a certain time during the flight. Inside the nose cone, he loaded the satellite onto a huge cocked spring which, once the nose cone was gone, would uncoil and hurl the satellite into the sky. It was nothing more complicated than that. And now I was totally hooked.

I knew I had to tell this story, so I put in my request for a Russian visa. I was also granted an appointment with the Russian Ambassador. He spewed forth the usual propaganda version of Sputnik, then warned me that I couldn’t just go walking around Moscow knocking on doors hoping to meet people, that Moscow was not New York. But this was the era of perestroika and glasnost, so as soon as I got to Moscow, I did exactly what he said I couldn’t do. I started knocking on doors.

One of those doors was the head office of the KGB. The people I met there were, to say the least, highly suspicious. But when I reminded them about perestroika and glasnost - concepts of openness and transparency that had created such confusion in a society where, since the Revolution they'd thrown folks into gulags for openness and transparency - none of the apparatchiks knew what to do. (Spoiler Alert: Today if you ask for stuff they sell it to you for cash.) Imagine my surprise, then, when a senior guy eventually decided to play along and gifted me files, making me among the first, if not the first, American journalist to get officially classified documents out of Russia. That is, without winding up in prison.

One of the documents I walked away with was the actual report that the KGB made to Khrushchev documenting the American panic to Sputnik. Encouraged by that, I continued knocking on doors. And they continued to open. I spoke to people who worked for Korolev, visited his office and design studio, and spoke to members of his family. I also spoke to members of the Khrushchev family, and visited his old dacha outside the city. That’s where he was, fast asleep that night in October, when Korolev phoned to announce, the missile worked. Khrushchev was pleased. When Korolev added, oh by the way, the satellite is in orbit and beeping, Khrushchev matter-of-factly mumbled, I never thought it would work, hung up and went back to sleep.

Three days after Sputnik was front page news in every newspaper in the world, the most prominent journalist in America, the New York Times’ James “Scotty” Reston, sat down for a one-on-one with Khrushchev who insisted that he had hundreds of more Sputniks ready to go.

It was a bold faced lie. And when I spoke with Reston about that interview, he even said he wasn’t sure Khrushchev was telling the truth. Putting it into some context, Reston dutifully reported it anyway.

What he didn’t know, until I told him, was that right after he left Khrushchev’s office, Korolev was summoned. Seeing Reston’s reaction to Sputnik, confirming the KGB report I had about the panic in the United States, Khrushchev asked his missile designer, what can you do next? Korolev suggested, how about we put a dog in space? Khrushchev told him, you have a month.

Reston’s reporting understandably heightened tensions in the States. But not in the White House here Eisenhower and his CIA chief, Allen Dulles, both knew the Russian missile launchers we’re empty.

So the question became, should we tell the American public that there is no real threat, that Sputnik is of no military significance? That Khrushchev’s statement to Reston about having hundreds of more Sputniks ready to go, was just Russian bluster.

Dulles wanted Eisenhower to reveal it. And up to an hour before Eisenhower was scheduled to make that announcement live on television from the Oval Office, showing U-2 spy plane photos of Baikonur to prove there were no more missiles ready to go, he backed out. He felt that revealing what the CIA knew would tell the Russians that the United States was illegally flying spy planes over the country and taking pictures of their empty missile launchers.

Ironically, the only people who didn’t know about the U-2 missions over the USSR were the American public and the Russian public. The Russian military knew all about it and, as my new Russian friend assured me, they were doing whatever they could to shoot it down.

Eventually they did.